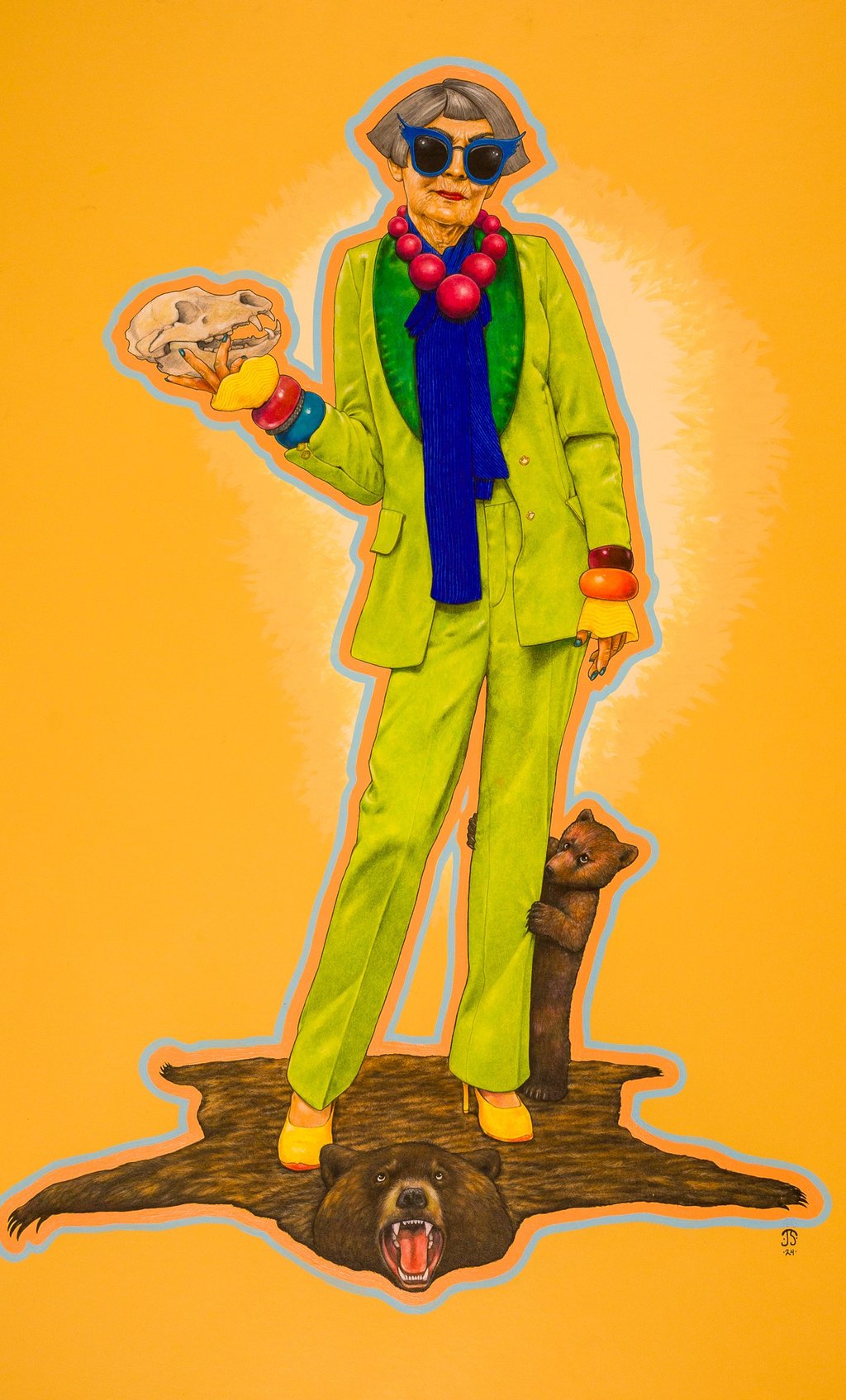

Oldilocks

24x30 Colored Pencil/Acrylic

Golidlocks was originally a tale simply called The Three Bears, in which a miserable old woman basically ruins these poor bears' lives and enjoys doing it. Why? Well, why not? This was entertainment in the 1800s.

Story

Gertrude Goldilocks had been perfecting the art of strategic home invasion for forty-seven years, ever since her husband ran off with a traveling snake oil salesman and left her with nothing but a talent for finding fault and an encyclopedic knowledge of other people's weaknesses. The transformation from heartbroken housewife to professional menace happened gradually – it started with "borrowing" a cup of sugar from neighbors who weren't home, evolved into rearranging their furniture "more efficiently," and eventually blossomed into full-scale domestic terrorism disguised as helpful criticism. By the 1840s, she had developed a sophisticated system: scout the house while the family was away, sample their food, test their furniture, and leave everything just slightly wrong in ways that would drive them slowly insane. The bears were simply her masterpiece – a family so obsessively neat and routine-oriented that disrupting their morning ritual was like conducting a symphony of psychological warfare.

The bears, of course, were not actually bears but the Bernstein family, German immigrants who had the misfortune of living in the cottage next to Gertrude's ramshackle boarding house. Heinrich, the patriarch, was a furniture maker whose pride and joy was the three chairs he'd crafted for his family – each perfectly sized and sanded to ergonomic perfection. His wife Brunhilde took great satisfaction in preparing their morning porridge to exact temperatures, and their teenage daughter Ursula had developed an almost ritualistic approach to bed-making that bordered on the obsessive. Gertrude had been watching their morning routines through her kitchen window for months, taking notes on their schedules, their habits, their little domestic satisfactions. When she finally made her move, it wasn't random destruction – it was precision-engineered to destroy everything they took comfort in.

The morning of the infamous porridge incident, Gertrude waited until she saw the family leave for the weekly market, then slipped through their unlocked back door with the practiced stealth of a woman who had made chaos her calling. She ate Papa Bear's porridge not because she was hungry, but because she knew he prided himself on the exact ratio of oats to milk. She sat in Mama Bear's chair and deliberately loosened one leg, knowing it would wobble in the most maddening way. But breaking little Ursula's bed was her crowning achievement – not an accident, but a calculated act of vandalism designed to shatter the girl's sense of safety in her own home. When the family returned to find their sanctuary violated, their routines destroyed, their trust in the world fundamentally shaken, Gertrude was already back in her kitchen, watching through the curtains as they discovered her handiwork. As she'd later confess to her diary, "Happiness is so insufferably smug. Someone has to remind people that comfort is just an illusion waiting to be shattered. Might as well be me."